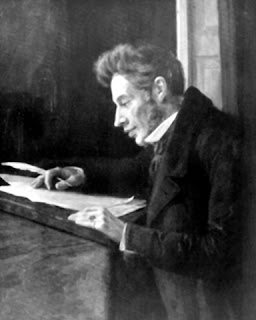

During my senior year of college (Wheaton, IL), I was introduced to Søren Kierkegaard's religious philosophy. As happens with many people, the first book of his I read was Fear and Trembling. While it's his most "famous" work, and the book most associated with his name, it's probably one of his more perplexing books. Nonetheless, it drastically re-oriented my thinking about faith and Christianity.

I had recently experienced an "epistemological crisis," of sorts; wondering whether Christianity was true after all, whether my faith was real (or just a hand-me-down), and whether, in fact, I could be confident that any of my beliefs matched reality. Kierkegaard helped me understand that faith, by its very nature, is meant to involve struggle. Doubt is and integral part of faith. Doubt is not necessarily sin. God does not want us to flounder in unbelief and apathy. He wants to stimulate in us the passion of conviction. Conviction is very different, though, from certainty. While someone who is certain can be passionate (and they often are, to disastrous results), the believer who is confident and convinctional about their beliefs is not as easily tempted toward dogmatism and is not as prone to making idols of their conceptions of God, their interpretations of Scripture, and their approach to the Christian life. They also make room for the convictions, beliefs, and distinctive "angularity" (particular shape of their humanity, or their "self") of others--even if they aren't persuaded by them.

The authentic, passionate, convictional believer is out "on 30,000 fathoms of water," and is better positioned to trust in God rather than in their own conceptions of God, their own ideologies (read: idols).

Kierkegaard helped me then (in 1995) and he still helps me today. That's why I'm glad to have the opportunity this Sunday (5:30 pm) to speak on the topic, "How Kierkegaard Can Help Us," at the Soulstice Service of Berean Baptist Church (309 County Road 42 E Burnsville, MN 55306). If you're in the area, come by and check it out. And if you bring in this add, you'll get 5$ off.

2 comments:

The plurality of your question struck me. I might have wanted to ask the question, "Why Kierkegaard Can Help Me?", given the current reading that renders Kierkegaard primarily interested in particularity. To avoid this insular reading, I wonder: does Kierkegaard help us recover 'confession' and the notion of confessional theology?

I wonder if 'confession' as a theological concept gets us more mileage than 'conviction'. Kierkegaard calls us to a life of passionate subjective agency faithful to our confessions, thus demanding that we actually make some confessions, that we actually make some claims about the God, the world, and the divine relation to humanity. Confession avoids some of the epistemological difficulties brought by 'convictions', while suggesting that our empassioned subjective confessions about the world must not only be lived out faithfully but must also be 'owned' in a very public way. In this way, we are able to read Kierkegaard more as a public theologian, concerned as much with the universal as the particular. (Assuming of course, that you want to argue that 'Kierkegaard can acually help US, not just Help Me.'

Silas,

Good point re. the plurality of the question being in apparent disjunction with the individuality of my actual narrative: "how Kierkegaard helped me".

I suppose at one level your question could be posed this way: Does Kierkegaard have more affinity with the post-liberal or the post-conservative project? As you know, my dissertation argued for the latter (contra Tim Polk's Fishean and Lindbeckian reading).

But more to your point, I do like the "confession" concept in some ways more than "conviction" or "confidence," because it grounds the epistemological question in history and tradition. My "conviction" doesn't just come from nowhere; I "confess" with the church, what the church (my tradition) has always(?) believed.

However, while appealing, I think it is hard to argue that this is what K was doing. He was intensely interested in particularity and in the angularity and passion of the individual "before God." Now, in another context, it's possible, I think, to take Kierkegaard's insights in the direction that you suggest, utilizing Works of Love in particular, as well as his own obvious faithfulness to his own tradition's confession. But that's an appropriation question, which is, of course, the most significant, and, ironically, the most Kierkegaardian!

So, I'm back to thinking through your suggestion again as a viable alternative...

Post a Comment